Mark Warschauer, Professor in the Department of Education and the Department of Informatics at UCI and a long-term reader and occasional guest author here and on EduTechDebate.org, recently presented a paper which included some interesting insights into the OLPC project in Birmingham, Alabama.

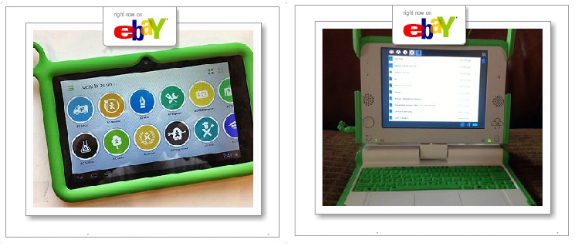

The paper is called Netbooks and Open Source Software in One-to-One Programs and compares three projects in Alabama, Colorado, and California. Whereas two of them follow what Mark calls the "Maine Model", given that they followed similar principals as the widely known 1-to-1 computing in education project started in Maine in 2002, the one in Birmingham, Alabama is more closely aligned with OLPC's approach:

"In line with OLPC principles, learning was viewed as stemming from young children's ownership of a radical new children's machine, rather than through a systematic pedagogical or curricular reform."

Unfortunately the actual implementation left much to be desired with the who-is-who of common ICT in Education implementation oversights being present in the form of a lack of attention in the areas of

- teacher training

- curricular development

- Internet connectivity

- technical support

- maintenance

The results are pretty predictable with few teachers using the XOs in class, students in many cases not even bothering to bring them to school anymore, and many machines simply being broken.

Now some people will point out that giving each child a laptop mainly impacts learning outside of school. However the paper indicates that this isn't necessarily the case:

"Students enjoy using the laptops at home, but, without their integration into an educational program, there is little evidence of substantive social or educational benefit achieved from home use."

In the paper's postscript it is mentioned that the current Mayor of Birmingham has cut the funding for the OLPC project for the moment. In case the project were to be revived it should probably take a close look at Mark's observations as well as do what other OLPC projects have done to avoid some of the common worst practices in ICT for Education.

Can we trust a three pages Google sponsored paper ?

First of all I'm not sure why Google sponsoring the paper would make any difference. Microsoft, Intel, okay - but Google doesn't really have a stake here IMHO.

Secondly, in any case the component that's more important to me is that I trust Mark Warschauer, probably even if he were sponsored my Microsoft, Intel or OLPC itself;-)

I’m sure that professor Warschauer has based his conclusions on hard data and extensive factorial mathematical analysis. Unfortunately they are not present in the cited meeting abstract where data are described almost anecdotal.

I think we should reserve judgment for the full peer-reviewed paper to see what conclusions will be validated there.

I think that is a fair point. The next lengthier paper I have coming out will appear in the Journal of International Affairs (http://jia.sipa.columbia.edu/), set to appear on Dec. 6. It will discuss our own and others' findings from Birmingham, Uruguay, Peru, and Paraguay. A fuller paper on the Birmingham program is a bit down the road.

I'm not sure is related to the above but I have a question that i believe you should be able to address.

If I understand correctly computer penetration in the US for school kids is almost 1 to 1 and almost 60% of the schools have computers for their students.

To that extend an 1 to 1 program in the US (without further curriculum integration, extensive teacher training etc), is like studying the difference of 1 to 1 vs 2 to 1 (computers/child) effect. It is likely ( ;-P ) that this will not produce significant differences. How do you control for that?

In the same context, are practices and conclusion from a community already saturated with computers before the start of the program, valid/transferable to less developed communities? How do you decipher what's directly applicable and what is context specific?

I can understand that this may be part of a lecture or a long article, but if you feel up to it would be very interesting to hear it.

Thx.

Good questions. I would guess that well over 95% of US schools have computers for use by children. The overall ratio of students to computers in US schools is about 3 to 1. That varies from district to district though. I think it was much lower than that in Birmingham before this program. However, it is true that most children in Birmingham had acess to computers outside of school before they were provided XOs, usually at home but also at other places. (One of the surprising findings of Shelia Cotten's pre- post- survey findings in Birmingham is that students tendied to use computers more for homework, research, and online content production before thy got XOs as compared to after.)

You are right that you can't generalize from a US context to a very different situation like rural Peru. One could hypothesize that children in Peru get more benefit because they have otherwise less access to technology. One could also hypothesize that children in Peru get less benefit because the sociotechnical infrastructure to support computer use is weaker. In spite of differences though, ther have been some common patterns of XO use in different contexts (that I won't get into here as this is already a long response.)

Interesting article, but I have some questions for professor Warschauer. I did some research in Uruguay, inside the context of OLPC: I concentrated upon the topic of integration of disabled children in mainstream classes and not on the overall education results. By the way, I had to analyse the good and the critical points in plan Ceibal: the majority of the teachers I interviewed complained about the lack of training for them. Even if many of them also complained about the slow and inefficient XO laptop, they seemed to put that problem on a second place. As to say: training came before the instrument. Was it like this also in Birmingham? What if the one-size-fits-all laptop happened to be implemented in a Maine-like project? Can we safely assume it would make it a worst project?

In fact, the XO is hackable, and the 1.5 version of the hardware allows proficient use of a mainstream linux distribution side by side with gnome... what makes it different from the EEEpcs?

I can't sort out which was the bigger problem in Birmingham, since it was a combination of things. Hard to determine which was most important.

As for the XO, it may have advantages in some developing countries, due to its low power usage, but in a US context it was very problematic. It's keyboard is very fragile, screen breaks are frequent, there are problems with the trackpad and charging cord. It's limited capacity meant that it performed very sluggishly. It lacks an external monitor port for connecting to a projector. None of these things are related to the OS. Even in Uruguay, as you know, nearly 30% of them are out of commission due to breakage or problems, and more than 30% in poor communities.

What did you find in your study? Is the paper available?

Thanks for the answer.

My study was actually my PhD thesis, and I am closing it in these very days. The main outcome, with respect to mobility impaired children integrated in mainstream classrooms, was that they developed interesting social skills, partially contradicting the teachers' expectations which saw in the XO a mainly functioning-improvement tool.

It would be interesting to repeat such a study where the adopted computer is not the XO: I am now wondering how much the low performance of the machine influenced this (what would happen if they had a more powerful machine? Would hey prefer using it for writing and for searching on the internet rather than to chat and play with their peers?).

If you are interested, I can send you a copy of my thesis in a couple of weeks.