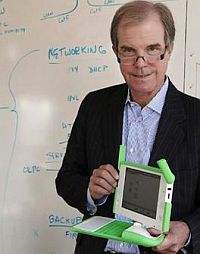

In 2005, Nicholas Negroponte, the founder of MIT's Media Labs, announced the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program at the World Economic Forum. The concept was simple and appealing: Innovate a $100 laptop and distribute it to children in the developing world.

No one can argue the power of getting kids access to computers/internet, and hence, access to a virtually limitless store of information, connectivity to the world and educational software. And for a technology optimist like Negroponte, the payoffs were obvious. But as the OLPC program has found out over the years, there is more to the success of Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) in Education, than just handing out computers to kids, and expect it to works its magic on its own.

To begin with, the premises and approach of OLPC program as articulated by Negroponte are fundamentally flawed. OLPC stipulates that laptops be owned by children over the age of six rather than by schools. Efforts to reform curricula and assessment are viewed by the program as too slow or expensive, and teacher training as of limited value due to teacher absenteeism and incompetence, so laptop implementation must proceed without them.

The program also believes that in the end, "the students will teach themselves on how to use the laptop. They'll teach one another, and we have confidence in the kids' ability to learn". The other flaw in this program is that the poorest countries targeted by OLPC cannot afford laptop computers for all their children and would be better off building schools, training teachers, developing curricula, providing books and subsidizing attendance.

Some OLPC Statistics:

- When OLPC was launched in 2005, it predicted the initial distribution of 100 to 150 million laptops by 2008 to targeted developing countries. As of August 2010, about 1.5 million OLPC laptops (XOs) had actually been delivered or ordered. More than 80 percent of these have gone to countries categorized by the World Bank as high or upper-middle income.

- Only two countries have implemented nationwide use of XOs in primary schools: Uruguay and the small Pacific Island nation of Nieu (with a total school-age population of 500).

- In Peru, after a first phase in which some 290,000 children in rural schools were given laptops, the program will reportedly be extended to the rest of the country on a per-school rather than per-child basis.

- In Rwanda, where only 7 percent of homes have electricity, the government has joined the OLPC program as a way to spur development, but has only purchased or had donated enough computers for fewer than 5 percent of primary school children in the country, and only a fraction of those have been distributed.

- The U.S. government bought 8,080 XOs for donation to Iraq but they never reached children's hands; half were auctioned off to a businessman in Basra for $10.88 each and half are unaccounted for.

The Main Issues with the OLPC program:

There are 4 main reasons why the OLPC program has not been doing as well as it had expected or hoped for: the affordability of a laptop program for the countries targeted, flawed expectations about the effects of implementation, problems with the design of the XO, and the realities of student use.

1) Affordability:

Though the initial goal was to sell the XO laptop for $100 or less, the sales price per laptop in a bulk order is about $188. The cost of implementing an XO program, including the purchase of laptops and other infrastructure, as well as development expenses, has been estimated at about $75 per student per year. Even a less expensive national program would be difficult to afford in a country such as Rwanda, which currently spends a total of about $109 per pupil per year on primary education.

2) Flawed Expectations:

In 2007, the Government of Peru ordered 290,000 OLPC laptops to be used individually by children in rural one-room schools, and ordered another 230,000 to 260,000 for future distribution. A preliminary evaluation carried out by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and an independent investigation both suggest that the program, though viewed positively by teachers and parents, is mired in infrastructure difficulties. A number of the country's rural schools still lack electricity access and those that do have electricity access sometimes have only one outlet in the principal's office, making charging--and subsequently using--the laptops nearly impossible. Most schools lack Internet access, further limiting how the laptops can be used.

According to the IDB evaluation, only 10.5 percent of teachers receive technical support and 7 percent receive pedagogical support for use of the laptops. Even when training was offered, teachers in one-room schools were often unable to leave their school to attend the training and were unwilling to travel to receive unpaid training during their vacation time. Some 43% of students do not bring their laptops home, mostly because teachers or parents forbid it out of fear they will be held responsible if anything happens. Facing these problems, Peru appears to be moving away from the laptop per child model. Upcoming deployment will be to schools rather than to individual children, where newly established Technology Resource Centers will house twenty Internet-connected XO laptops, a multimedia projector and a screen.

3) XO Design Issues:

The XO laptops have performed poorly in the field due to hardware/software issues, and has proven problematic for maintenance. Its screen was the first of its kind, but it is also expensive--$65 in Paraguay or $85 on Amazon.com, difficult to replace and proprietary; one cannot use a generic screen or one from another laptop model. The keyboard membrane, meant to be spill-resistant, is so thin that normal usage results in the membrane around keys breaking and keys falling off. The touchpad mouse similarly degrades with time. Other problems include an easily breakable charger cable due to shoddy manufacturing, the placement of the cable on the side of the transformer rather than the back, and the lack of a standardized cable between the transformer and the power outlet

4) Realities of Student Use:

Studies to date indicate that XO laptops are, for the most part, little used in schools. In Uruguay, only 21.5% of teachers report using XOs in class on a daily or near daily basis for individual student work and 25% report using them less than once a week. In Peru, usage appears to diminish substantially within the first few months: 68.9% of teachers in Peru who have had the XOs for less than two months reported using them three or more times a week, but only 40 percent of teachers who had the XOs for more than two months reported that level of use. Studies in Haiti, Uruguay, the United States and Paraguay suggest that many children, especially the most marginalized students targeted by OLPC, are not able to exploit the potential of the XO on their own, whether using it at school or at home.

An IDB study of a pilot project in Haiti noted that a large number of participating students reported experiencing a ceiling effect on learning with XOs, as students avoided aspects of the XO that were confusing or problematic to them and thus engaged only in simple activities with which they were most comfortable. A national evaluation study in Uruguay pointed out the challenge of reaching the portion of children who excessively or exclusively use the XO as an entertainment device. In Birmingham, students after getting the XOs, spent substantially more time in online chat rooms. Our interviews and observations in Paraguay suggest that a minority of youth are making use of the XOs in creative and cognitively challenging ways, and a majority using them only for simpler forms of games and entertainment.

Conclusions:

The OLPC program has the correct intentions, but a flawed philosophy and approach. Just deploying technology and expecting to work its magic is not the way to go. For the diffusion of the technology, it is crucial that we adopt to the local practices and constraints. Social and political structures also play a crucial part in the diffusion process, and one cannot ignore that. ICTs have an important role to play, and can be a catalyst in improving the access and quality of education around the globe. But it is NOT the "silver bullet" that will solve all educational issues. It has to be used as a complement to, and in conjunction with the political, social and economic structures of society, and one has to realize that other critical factors of the educational system need to be fixed before ICTs can work their magic.

This post was originally published by Pritam Kabe as ICTs in Education: The "One Laptop Per Child" Program - Right Intentions but Flawed Approach

OLPC XOs currently cost much less than printed textbooks in all but the poorest countries, even including solar power units on the roofs of schools, or other renewable power sources. Costs for newer models are decreasing, while capabilities are increasing and power consumption is being cut drastically, resulting in much lower cost for supplying electricity.

The curriculum and teacher training projects are under way, as documented here in OLPC News articles, and on the Sugar Labs Wiki. Negroponte was right that XO deployment should not wait for them. Otherwise they would never begin.

Pritam Kabe sees only some glasses, all half empty or worse, in usage statistics. I see many more glasses half full or better. In particular, usage statistics for teachers tell us nothing about what the children are learning about the world on their own with their XOs, and sharing with each other. Or what they are learning about a technology and culture of sharing.

Getting the right answers to the wrong questions is one of the most useless forms of inquiry.

I can't speak for other countries but in Australia, at least, OLPC is doing everything right, and making a difference to Aboriginal children.

I've seen it first hand and, perhaps, the difference is the way they educate teachers in how to integrate the XO into the classroom, how they use the community elders to encourage kids to value their XO, and the like, as well as clever imaging of the systems before despatch and great support too.

I'm never sure what to make of essays like this, which fling a bunch of statistics and data from different contexts together, including some misguided statements, without a single reference.

A requisite rebuttal to the traditional error: OLPC does not believe in silver bullets, or in "deploying technology and expecting it to work its magic [without] adopt[ing] to the local practices and constraints." The org does more to support local customization than any tech or ed group I know, and often publishes links to details of its training materials and sessions -- again, unusual.

Yes, of course this sort of educational program must be complemented by other social and national development. (Among other things, olpc efforts work well in coordination with electrification and rural connectivity programs.)

Other notes: The idea that the monitors are comparatively expensive or hard to replace is silly. As far as I know they remain the least expensive displays of their size, and can be replaced by a novice in under 5 minutes...

You can add Peru and Kosrae to the list of states reaching all of their students (and spell Niue properly :). Yes, Peru has found its own way, including a different sort of shared ownership of laptops in urban schools -- this sort of experimentation and exploration in deployment is important. As with their investment in shared robotics, we should applaud Peru for steadily trying new things.

From something I posted in November 2009: http://listcultures.org/pipermail/p2presearch_listcultures.org/2009-November/006250.html

My analysis of the OLPC project:

* They used the wrong processor at the start (the ARM they are choosing now would have made the system cheaper and improved battery life).

* Sugar was a disaster -- not because of the aspiration, but because it should have been an "add on", to add social networking or simplified user interfaces on top of Gnome (or KDE) for GNU/Linux; as it was, Sugar prevented software developers like me from developing software for the OLPC because it made the OLPC a tiny niche compared to GNU/Linux, plus Sugar was a moving target.

* Emphasizing Python for writing all the applications made the whole thing slow; OLPC should have stuck with plain GNU/Linux so apps were in fast by being mainly in C (given the slow processor), or moved to a Java system as soon as that became "free as in freedom", or alternative gone entirely with Squeak (which always had an open ended education focus and was end-user modifiable). Even just building on Forth might have worked out better than Python, in which case GNU/Linux would not have been needed at all, simplifying the entire project to Forth plus what people built on top of that. Forth can be implemented in a cheap FPGA instead of a CPU, which might have brought hardware costs down even more.

* The hardware focus was misplaced. Software really was where it was at. A simple reading tutorial program and a simple math tutorial program that were self-paced would have probably been a bigger net benefit.

* The hardware fit with the culture was wrong (not to mention exposes children to theft risks). Village cultures would have benefited more from village PCs, so, a centralized public library-like facility for the village with a satellite internet connection and one hardened PC computer plus many cheaper terminals (even cell-phone like if needed to reduce costs).

* The decision not to sell to the industrialized world on a consistent basis was a mistake, because that would have been a way to lower costs through increased volume as well as interest more developers.

I bought two OLPCs (well, four :-) to try out for development. I did port some code to the OLPC (from our PlantStudio software) but it was very slow in Python. I might have improved the performance, but it did not seem worth it due to Sugar and the time it would take to Sugarize the app. Ultimately, Sugar was too much of a hassle to deal with constant changes with and too poorly designed IMHO at the time, even as it continues to improve and even as the ideas in Sugar are good. As a developer of free software with limited time doing this on my own time, why should I spend time developing for Sugar when I could just develop either for GNU/Linux in general or for Java? In that sense, the OLPC project alienated itself from the developer community, misjudging how developers would look at this. As I see it, having to triage my efforts, by poor strategy, OLPC and Sugar forced me to make a difficult choice -- I could spend my time making an application just for the OLPC with an installed base of, at most, a million materially poor kids (worthwhile, obviously), or I could make software (or, it turns out, content) for hundreds of millions of people who could run Java or tens of millions who run GNU/Linux, with the expectation that in a couple of years, millions of materially poor children when other projects just put regular GNU/Linux in their hands or Java based computers. It was a difficult choice. Having to even think about it pretty much stalled my work towards an OLPC app. I think many free software developers would not even have gone that far.

More than US$20 million dollars was spent on the OLPC project just for hardware development and software infrastructure like Sugar. I think it has very little to show for it in that sense (even as I think our society would be justified in trying 1000 OLPC type experiments, so I think more money should go into this area despite the problems I outline). The new quirky OLPC screen is rapidly becoming obsolete compared to eInk digital paper. That is the nature of fast moving hardware these days. The hardware design is already being discarded (with finally a move to ARM instead of an x86 based processor as anyone with embedded experience might have told them at the start). The software is incomplete and buggy, while there are literally thousands of GNU/Linux applications that kids could have been using but on a practical basis cannot because Sugar makes that hard, and otherwise there might have been even more educational tools inspired by the OLPC but made for GNU/Linux in general if developers did not have to wrestle with Sugar (and its many incomplete incarnations). The OLPC pricing model failed in the sense that anyone in the consumer electronics industry could have told Negroponte that only one third of the retail cost of products is the hardware (the rest is supply chain costs, profit, recouping R&D, or advertising and so on), so pricing a retail US$600 netbook at US$200 from huge orders through a non-profit was no great magic. (And there were cheap classroom computers as well as smart cellphones even when the OLPC project started.)

In the long term though, yes, I think there will be one (or many) computers per child. And overall, OLPC was a worthwhile attempt, even despite it making just about every obvious error such a project could make (like they went out of their way to fail, and were still a bit of a success anyway. :-) We just need many, many more such attempts. To reiterate, because I said so much bad about Sugar, I think the goals of Sugar made sense, they were just implemented in an unfortunate way, to get in the way of all use of software, rather than as as add on.

As the "hole in the wall" project showed, and it existed before the OLPC project, illiterate children in materially poor circumstances can pick up common computer interfaces very quickly.

http://www.hole-in-the-wall.com/

Repurposing old computers might make a lot of sense too. IBM and other big companies every year take literally millions of older laptops and crush them. (I had a plan to turn those into display walls and built a prototype at IBM Research.) Same for older cellphones that could be repurposed (some people edit Wikipedia from their cellphones), and maybe even reprogrammed as terminals with a local network. In two to three years or so, the current generation of smart phones just coming out like the Google Droid will be discarded for something new, and those might make terrific cheap education platforms.

http://phones.verizonwireless.com/motorola/droid/

So, Droid is a more tempting platform to me for educational software than the OLPC and Sugar in that sense of a big market. :-)

Imagine, Google and Verizon could even make a promise now to customers -- buy your Droid through Verizon, and in two years, if you continue your cell phone plan, we will give you the latest Droid version and if you return the old one to a Verizon store, we'll send it to materially poor kids loaded with educational software that teaches them how to read, write, and do math. And with bluetooth, and WiFi, the Droid could even have some software that works along the lines that Sugar aspired to do, with kids collaborating together. What a deal -- and it might greatly boost current sales. :-) Maybe someone should forward this note to someone they know at Google or Verizon? :-) Seriously, what US teacher would not buy a Droid over an iPhone knowing it was going to teach some poor kid to read in two years? (Of course, Apple might eventually have to follow suit. :-) And that gives me and the rest of the free software developer world two years to write all that free software for those kids. :-) Of course, it might be nice if Google or Verizon helped some of those free software developers to write lots of cool stuff (millions of dollars in support for education software could just be considered part of their advertising budget). But it might happen even if they did not directly provide support, because a lot of developers might see the potential, as I did. And it might help Droid sales even now, for parents to hand their Droid to their kid who was learning to read or write or do arithmetic, and it would help the kid. Parents might even buy a Droid for all their kids, and think that in two years, those Droids would also go to materially poor nations. This project might even help boost the economic recovery in the USA. And of course, there are many Android devices beside the Droid, so all of those might benefit as well from educational software. And, the Android platform already runs well under almost any PC OS in emulation. So, any free software made for the Android will also run right now on any desktop or laptop, and likely that integration could be improved even more over time. I'm using an Android emulator on the Mac for playing around toward an Android app I'm thinking of releasing as non-free at first to pay the bills -- as sad as it is for me to go back to writing non-free software. :-( At least if I sell it myself, I can later free it, whereas if I write proprietary stuff for others as I have in the past, it can never be freed.

Here is why I feel somewhat qualified to criticize OLPC, :-) a post I made about a US$100 educational laptop from 2001 (yes, probably years before it was a gleam in Negroponte's eye :-), and I still think my design outlined there makes a lot of sense (except a SSD would be better, true): :-)

"[unrev-II] The DKR hardware I'd like to make..."

http://www.dougengelbart.org/colloquium/forum/discussion/0754.html

"Developing and then deploying this sort of device is the sort of thing the UN or a major foundation should fund (if they were on the ball). But luckily, there is hope from toymakers!"

So, I should now add, "But luckily, there is hope from the cellphone makers!" :-)

Seriously, this sort of planning for a formal transfer of millions of Droids to the materially poor world in two to three years could shake the foundations of our global society in a good way. (A bit of a pun intended there too -- foundations, shake the money tree, get it? No? OK, so I'm a programmer, not a comedian. :-)

===

By the way, lest one think I go around only bashing the OLPC program, here is a suggestion by me that Princeton Univeristy be dissolved and the endowment spent on educating the poorest one billion children of the world instead through using OLPC machines:

http://www.pdfernhout.net/reading-between-the-lines.html#A_Modest_Proposal_for_the_use_of_Princetons_assets_for_the_maximal_public_education

So I believe in the constructivist concept, just not the particular implementatiton.

OLPC editors, do you realize that this essay is "lifted" (in some parts summarized, in other parts repeated verbatim) from our own paper:

Warschauer, M., & Ames, M. (2010). Can One Laptop per Child save the world’s poor? Journal of International Affairs, 64(1), 33-51. http://jia.sipa.columbia.edu/files/jia/033-051_Warschauer_bluelines.pdf

@Morton, if you wish to see the references, you can see them there.

Hi Mark,

i wrote this personal blog as a part of my studies on International Development at Georgetown.

And i have mentioned your paper as a reference in the bibliography.

-Pritam.

Hi Pritam,

Yes, I noticed that you cited our paper in your blog. I was surprised to see that that reference was excluded from the OLPC repost (not your fault, I'm sure). And thanks for your interest in/support of our perspective and research.

Beyond that, though, as a scholar, you may want to consider a bit the way you cite things. Though you cited our paper, there was no indication that you actually quoted from it extensively (without any quotations marks) and that your entire blog was basically quoting (in some places) and summarizing (in other places) our argument. In cases like this, it would probably be good at the top to indicate that you recently read a piece that you felt was valuable, and that you would like to summarize its arguments (and include quotation marks for parts that you quote).

I think this approach will be more helpful to you in academia.

Good luck with your studies!

Mike, thanks for the inputs.

I'm new to academia, and this was one of the first blogs i wrote. Since then, I've learnt about the technicality of quoting and footnoting; but didn't get the time to go back and edit my initial blogs. Sorry about that.

But i appreciate your feedback. I learnt a lot from your OLPC paper.

Regards,

-Pritam.