I am Mary Hooker and I work as an Education Specialist with a small NGO called the Global eSchools and Communities Initiative (GeSCI). GeSCI was established in 2004 with a mandate to provide strategic advice to Ministries of Education (MoEs) in developing countries on the large-scale planning, integration, and deployment of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Education Systems.

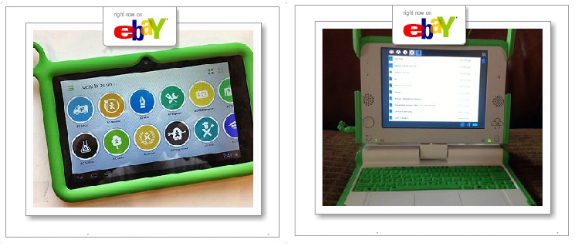

I developed the paper on 1:1 technologies in order to initiate reflection, commentary and dialogue on the emerging debate surrounding the introduction of saturation technology approaches such as the OLPC in education systems in the developing world: 1:1 Technologies/Computing in the Developing World: Challenging the Digital Divide.

Mokurai's commentary that the paper is 'very conventional, and not at all helpful in coming to grips with OLPC innovation and its consequences' is both useful and intriguing in its relation to my rationale for writing the paper.

Useful in that my purpose in the paper is essentially to examine what happens when traditional education systems attempt to 'come to grips' with new technology innovation such as the OLPC, with its cybernetic untraditional ideals. Intriguing in that my focus in the paper is about unveiling the 'consequences' in terms of the tensions which emerge when such traditional and untraditional systems converge - tensions which can appear problematic if not unhelpful - but if they are handled constructively they can bring about development through expansive learning.

'Tension' is an underlying leitmotif that I explore throughout the paper.

I use an Activity Theory framework to interpret findings from preliminary studies on the use of 1:1 technology in the pilot introduction of OLPC and e-book software in the conservative environment of the Ethiopian Educational System. Applying the framework revealed the underlying tensions which emerged between the traditional and non-traditional boundary fields and the struggle between players in the expanded community of teachers, technologists, designers and advisors over how the new approach inherent in the technology should be interpreted and implemented.

I draw comparisons with an historical study account on the struggle to integrate Logo as a computer language experiment for dynamic change in mainstream education systems in the US and UK in the 1980s and 1990s.

Tensions can be disconcerting as they push the boundaries of established norms; but tensions can also push systems towards reconceptualization of norms and a wider range of possibilities that can stimulate expansive transformation. In the final section of the paper, I draw attention to a series of policy issues which 1:1 tension fields raise in both developed and developing contexts, and which push for a broader more fundamental response framework - for defining what are the educational objectives that will drive the technology integration, for outlining teacher preparation, for identifying supportive educational structures and curriculum frameworks, for clarifying infrastructure and maintenance and for pre-empting financial considerations for system wide implementation.

It is GeSCI's view that to take full advantage of technology options such as 1:1 saturation and to direct their maximum use for the benefit of all students, there needs to be such a clear framework which sets the scene and provides the enabling environment for the technologies to be integrated, deployed and used to their fullest potential.

Ms Hooker, your paper provides a cogent round-up of approaches to 1:1, situates these effectively in the overall history of educational computing, and draws concretely on the Ethiopian experience as a kind of case-study illustrating the 'tension leitmotif' that you mention above.

The difficulty, with all respect, is that in common with many academy-style articles, the paper spends a huge amount of time providing evidence (and citations) to support positions and outcomes that can be pretty easily anticipated. Your article, in fact, suggests that the tension experienced in Ethiopia is not all that different from tension experienced in schools in the US and Europe over the last 40 years, beginning with the introduction of Logo. The ubiquity of the technology has changed, both within and outside of schools, which has shoved the point of tension toward the sites of the "digital-divide." But the tension itself isn't that different.

What are the takeaways from your article? More and better TPD, more and better integration, more informed budgeting? These points aren't arguable. (Except, of course, the original OLPC implementation _did_ argue exactly against the need for these kinds of inputs! Now, that's tension for you.)

What _might_ be more helpful would be comparisons of successful large-scale incrementalist approaches, such as World Links (OK, semi-successful [perhaps Fundacion Omar Dengo would be a more valuable choice]) with developing-country experiences of the saturation model advocated by OLPC and other 1:1 promoters. But again, the key to making work of this sort helpful would be to pull something out of this mash-up that isn't a story foretold.

There are a lot of good insights in this paper concerning the culture clash between traditional instructionism and olpc's radical constructivist approach.

However, something essential is missing concerning the larger context. The paper talks about the motivation for adopting olpc being overcoming the digital divide. Actually, much more important than that is that in a great many developing countries, the instructionist approach is failing at achieving even its own objectives. School attendance rates are low, students drop out after only a few years, and so even simple literacy is not achieved for the population as a whole.

There are a number of seemingly intractable reasons for instructionism's failures. Olpc is instead taking a radically different approach, using the computer to make education much more interesting and also less labor-intensive on the side of treachers.

And the X0-1 is only the start. The goal for the X0-2 is full human-power and a $75 price, low enough that many families could buy it on their own. Load it up with self-instructional software, and much education is simply going to move outside the school. That is hardly idea, but it is considerably better than any other approach that might actually work.

Negroponte hints in this direction, but doesn't say it explicitly because he is for now busy selling to the very education ministries that he is going to wind up partially undermining. I think educational researchers are a bit too committed to the present institutions to appreciate where olpc is going.

What amazes me the most is that so many in the OLPC camp seem to think they can dump a whole load of computers into a clasroom in a developing country and: voila, eduation... meanwhile in our own back yard we still haven't managed to integrate this level of technology into the classroom. how far have we got in most 'advanced' schools in the UK - interactive whiteboards and thats about it.

What Ms. Hooker's paper really seems to be saying, in a lot of very complex language (worthy of a PhD i'm sure), is that until the the teachers know what to do with this technology there is going to be a lot of tension. For tension read confusion.

Well that's hardly surprising now is it.

Of course the kids will have a lot of fun playing around on little laptops (until they break), just like the kids in a couple of the pilot schools in England are suddenly "delighted" to have a Sony PSP to mess about on. Who wouldnt be? But is that really education? Nope. Well, if you believe that all the next generation needs to know is how to use a computer, then i guess its education.

Why not just give them electronic book readers and a few dozen electronic textbooks. No software void to bridge and no puzzled teachers wondering what they're supposed to teach. And voila: no tension.

The principal that BECAUSE we can THEREFORE we must should be seriously questioned. Just because we CAN give kids laptops (and actually that still is debatable) doesn't mean that its the right thing to do. When will people realise that if you're just able to crawl, learning to walk would actually be quite a good next step (excuse the pun).

I suspect that if 10CC were re-writing their 1976 classic Art for Art's Sake today, it would be entitled Technology for Technology's Sake. And it would be just as cynical as it was then.

Dear Ed, Jeremy and Eduardo,

Thank you for your comments on my paper.

I like the discussion you have opened and would like to add my comments to your reflections.

Ed, I would hope that the paper is not so much about a “story foretold” but about a story revisited. A story indeed that I was a part of as a young primary teacher in Dublin in the early 80s who introduced Logo as an ‘extra-curricular computer activity’ to my students and was pleased with the pretty pictures they produced – a story that I would revisit again almost thirty years later as I joined my colleagues in a community of practice in a Dublin college (for a Masters Jeremy/ PhD maybe later if I have the energy!) to discover - through reading, reflection, discourse and inter-active analysis with my community - the beauty of the concept that is Logo – a microworld language and ‘object to think with’ that can transform our understandings of teaching and learning.

And as I listen to teachers’ stories in our partner engagements in the developing world - as they too grapple with the unfamiliar tools of the newer technologies – I am struck by practitioner “confusion” Jeremy that is all too familiar – and I believe that the issue may not be that teachers need to “know what to do with this technology”, but rather that teachers need to know what to do with this confusion. It is to question and analyse the education support systems that can enable teachers to reflect on the confusion and tension that technologies engender - in an environment Eduardo which both respects the traditional “instructionist” approaches and provides courage for the new “radical” approaches.

It was my intention then that the “take aways” from my article Ed were less about ‘more and better’ of this or that – and more about recognition of ‘confusion’ and ‘tension’ emerging from stories unfolding in education systems north and south as real opportunities for learning – learning which can enable the said education systems to incorporate technology in all of its potential for enhancing the learning of our students to the requirements of a 21st Century Information Age.