Walter Bender's question 22:

What "shoulders of giants" should we stand on? What is it that children should learn? Are there any universals? How do children decide whom and what to believe?

I've been providing what I think is a good answer to these questions for some time now but often the response is muted and contradictory. It's not my original answer, it originates from Alan Kay and his analysis originates from anthropologists.

The answer is not that children should learn universals but there needs to be more focus on what Kay has called the "non universals". From anthropological research of over 3000 human cultures, Kay presented two lists, the first were universals, the things that all human cultures have in common. This list included things like:

- social

- language

- communication

- culture

- fantasies

- stories

- tools and art

- superstition

- religion and magic

- case based learning

- theatre

- play and games

- differences over similarities

- quick reactions to patterns

- loud noises and snakes

- supernormal responses

- vendetta

- and more (about 300 of these have been identified across cultures)

What Kay said about this list, transcribed from his EuroPython 2006 keynote:

In effect anthropologists have been studying humans for about a Century now and firstly 3000 human cultures seem to be very very different. Then they start realising that they seemed surprisingly parametric. Every culture had a language, every culture told stories ... (goes through some of the items on the Universals list)

If you look at these you can see our modern internet culture - it's basically social, it enables us to communicate in various ways and so forth, basically a story based culture.

He then presented a list of non universals, the things that humans find harder to learn. This list was shorter and included:

- reading and writing

- deductive abstract mathematics

- model based science

- equal rights

- democracy

- perspective drawing

- theory of harmony

- similarities over differences

- slow deep thinking

- agriculture

- legal systems

What Kay said about this list:

What's interesting is to look for things that are not universal, that seems to have some importance as well. Most people have lived and died on this Earth for 100,000 years without reading and writing, without having deductive maths and model based science .... (goes through non universals list)

These are a little harder to learn than the ones on the left because we are not directly wired to learn them. These things are actually inventions which are difficult to invent. And the rise of Schools going all the way back to the Sumerian and Egyptian times came about to start helping children learn some of these things that aren't easy to learn. It can be argued that if you are trying to be utopian about education what we should be doing is helping the children of the world learn these hard to learn things. Equal rights is a really good one to help children learn. No culture in the world is particularly good at it.

The non universals have not arisen spontaneously, they have been discovered by the smartest humans after hundreds or thousands of years of civilisation. Hence, it follows that children need guidance in learning them, they will not be discovered by open ended discovery learning. There is an objective need for some version of "school" - where advanced knowledge is somehow communicated from those who know it to those who don't.

The resolution of the tension (between how children learn and the complex, non spontaneous nature of the development of advanced scientific or Enlightenment ideas) is to develop an honest children's version of the advanced ideas. For some of these ideas (not all) the computer can aid this process. Which ones? The list would include the laws of motion, turtle geometry, calculus by vectors, exponential growth, feedback and system ecologies. I think this should be the starting point or at least one of the starting points for thinking about how computers should be used in schools.

Part of the discussion here is establishing that computers are not currently used to their full potential in schools. IMO once the above vision of how computers could be used in schools is understood then it becomes obvious that they are currently poorly used in schools.

I've been wondering why this particular idea, the non universals, is not spreading more. I think it's because it goes against the culture of pseudo progressiveness which advocates that process is more important than content, that discovery is more important than knowledge and/or that education should be entertaining or at least laid back, that we shouldn't put too much pressure on children. The problem is how to teach the non universals without sounding like a "back to basics" fundamentalist. But that is a real problem that needs to be faced and resolved.

Is this an example of the unsane, the mental state where our ideas don't fit reality, the map doesn't represent the territory. We like to think of ourselves as mostly "sane" and contrast that with a few "insane" personal moments or the more permanent state of a few unfortunates. But the "unsane" idea makes room for a different self perception. What if more often than not we are unsane?

I've created a page on the learningEvolves wiki whose purpose is to expand and elaborate further on the meanings and educational implications of the list of non universals.

The author, Bill Kerr, teaches at Woodville High School in Adelaide, Australia. He previously contributed an article on "Tidying Up the Constructionist Suitcase" and his blog can be found at billkerr2.blogspot.com.

Think of a snowflake. Under the right conditions, water will crystallize into a unique shape. Take that environment away and you have water or ice. Each flake/crystal is unique and beautiful. Children are like that. They need the environment to be able to express themselves.

What they don't need (but we want to give them) are ice cube trays which make them conform to a convenient shape we want them to be in. Yes, cubes are convenient, but cubes are boring. Utilitarian, but boring.

So, don't force. Don't impose. Sit back and watch. Let them be. Just be.

Good lord, do you teach? If so, do you teach kids that are behind their peers due to a disability or poverty? If not, please stop.

I agree w/dickey45. Although Calvin's intentions are good, it short changes the adaptability, imagination, and inner strength of children even while learning within a structured environment. I think that there is more to what he is saying. Perhaps he just wanted to keep his comment brief.

I, on the other hand, have no problem being verbose.

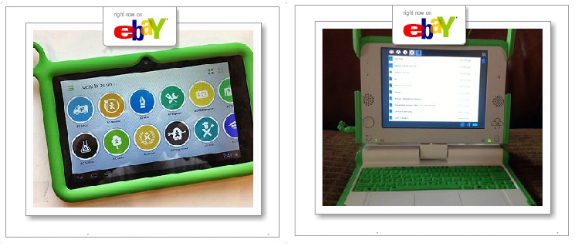

And to respond to your question, I believe the basic human behavior of selfishness is the primary cause that inhibits the sharing of non-universals. The OLPC is certainly an example of that. Just because Microsoft felt threatened by this effort, they've corrupted it. But that's something for another discussion.

First of all, I'm a firm believer in back-to-basics. We've enjoyed an enormous amount of REAL progress in the areas of medicine and science. These areas are REAL progress because they have done something to improve conditions for many humans. These acheivements have come from a generation that was taught using the basics.

The sad truth is that more REAL progress is not being made because of certain business, ethnic, or political interests.

And again, therein lies the answer to your question. The less people know, the easier it is to control them. Case in point is the mideast. The terrorists don't want schools there because the people will discover who the real terrorists are. And the people will find ways to resist them. It's a direct threat to the terrorists' way of life.

Large corporate business interests and political regimes are no different. They want to control everyone in their realm of influence. Again by example, patents and copyrights have become the weapon of choice for that purpose in the business world today. Hopefully 'the powers that be' will recognize just how inhibiting those are. This strikes me as an example of recognizing how important the non-universals are, but they don't want anyone else benefiting from the results.

Since we have become so profit oriented (ie, greedy), we have forgotten that true success comes from helping each other. The more skills we all have, the better our chances of survival. Through these skills we can learn how to develop sustainability.

But, the biggest influences in the world (mostly business) no longer understand or want sustainability. They want profit at any cost to the environment or to a culture.

Non-universals are the key to sustainability. They also can be the key to better understanding and relations between nations and cultures. They are the key to the survival of the human race. But they threaten the control of business and political regimes.

Finally, in my opinion, the most important of the non-universals are those ideals that promote and support harmony.

Having said that, I'm sure I sound like a full-blown socialist.

Oh well, nobody's perfect.

People talk and argue about School (is it worthwhile or a sort of sophisticated form of child abuse denying essential rights or freedoms of the child), curriculum (what new things should be in and how can we fit more in) and knowledge (What knowledge is important? Can we even know knowledge with any certainty?)

What strikes me as important about the non universals is that it provides some sort of scientific basis to answer these questions, that there is such a thing as progress, or Enlightenment, and the anthropological studies reveal to us what that might be.

Everything else seems to be just somebody's opinion in a world where everything feels they are knowledgeable about education because at some stage they went to school and / or had children.

The non universals do not provide an answer to all the problems of education. eg. How do we achieve an honest version of powerful ideas that is accessible to children? How do we motivate children to learn what adults believe is important? (Should we even try) If students say "this is boring" what do we say back to them?

Given the endless and politicised arguments about "back to basics" versus "discovery learning" the non universals list do provide for me a valuable starting point. What else provides such a starting point?

And that is a point that I failed to make. I went off on a tangent that was more a socio-political commentary than anything else. The point I wanted to make about non-universals is that they are the most fundamental definition of educational material.

When children enter school, they don't know what they don't know. What we hope to expose them to is the non-universals. And we hope "to start helping children learn some of these things that aren't easy to learn." These are the "inventions" (concepts, philosophies, perceptions) that have been developed over time by very gifted people that were very good at "slow deep thinking." (And personally, if I understand the use of this descriptive phrase correctly, this one seems to bridge the universal and non-universal groups.) Regardless of where that truly lies, we hope to encourage that same skill in our children.

I agree the non-universals list provides a definition of the basics that we hope to share with our children. Discovery only comes after you learn to "see." Not in the sense that you will "see" what everyone else "sees." That wouldn't be "discovery" then, would it? To me, "discovery learning" means to truly "see" the world around you in a very special way by using the skills of observation and analysis; ie, using the basics, the non-universals. Then the individual can experience new information that can be used to expand on an existing idea or perception. This is an exciting experience. This also is the response to the "this is boring" complaint. We must demonstrate the thrill of discovery that can occur as a result of staying the course to develop the non-universals.

A child left to themselves can discover, but they will not understand how to apply that new information in any way other than to interact with their immediate surroundings. Further, this happens in a random, haphazard, trial and error manner. There is no structure or frame of reference by which to understand the observations, the experience. Most parents hope to prepare their child for school by reading to them, playing with alphabet blocks, using sound toys (cows moo, etc). These efforts typically have structure although it might be loose due to the parents other responsibilities.

The culmination of education comes when one can take what they have been taught and can apply it in a new way. Some grade schools and most high schools create the opportunity for that experience by engaging in science competitions or putting on science fairs.

The adult, once they have completed an educational program (High School, Associates, Bachelors, Masters, PhD), has the skill set to challenge existing paradigms. This happens constantly. String theory is a good (or poor, if you don't agree with it) example of this in the world of theoretical physics. Someone has experienced a new impression of this realm. At some point, there was a departure from the status quo. This is a result of learning the basics, learning to apply the basics, then being encouraged to stretch perception beyond the borders of the status quo.

If nothing else, this new theory will challenge others (who agree or disagree) to rethink their own perceptions. The basics provide the oppotunity for new thought. The new thought then stimulates the imaginations of the other people with similar interests.

Another example of this is OJT; ie, On the Job Training. It's a hybrid of structure and practical application with the incentive of immediate compensation. The employer knows that the new employee lacks all the skills. But the new employee has a basic skill set. The employer becomes the educator by allowing the employee to learn and apply what they have learned. There are documented cases where the OJT employee has improved an existing process in a company because they "see" things in a new way even though their skill set is, by the employer's measure, basic.

Order in education should never be the overriding purpose. Some discovery is important. But it is necessary to provide a consistent educational experience that will have measurable results.

Maybe the people that support discovery learning are missing the point. Discovery learning has its place. But imagine an ADHD child in a discovery learning environment. That for me completes the discussion.

It sounds like you've been challenged by some people that support a "less threatening" learning environment where no student fails. If that's the case, good luck.

Okay, I've been verbose enough for tonight.

I find "universals" and "non-universals" to be a very poor choice of words. One would expect "universals" to be common to all cultures while "non-universals" only present in few particular ones. In reality all cultures have both, and supposedly "non-universal" ideas merely appeared or became popular more recently, and at different points in history in different cultures. While not every group of people has a large number of universally recognized scientists or political activists who participated in origination or any notable application of those "non-universal" concepts, there is awareness of them everywhere, yet nowhere it is "universal" enough across the whole society. To avoid the confusion between "not universal across all cultures" and "not universally popular across the whole society" I would rather prefer some word that would reflect that degree of the ideas' popularity within the society rather than something that implies "white man's burden" of bringing not-advanced-enough foreign society up to speed.

Teaching "non-universals" therefore is not about "educating the savages" whose culture supposedly lacks them what the name seems to imply, it's about teaching kids the ideas that no society throws in their faces on a daily basis, so school has to apply a special effort to teach those ("universally" useful and important) things when neither the rest of society nor spontaneous discovery by kids, are of much help.

hi teapot,

The term universals is well established from anthropological studies. My understanding is that the universals have been around in human cultures for hundreds of thousands of years, whereas the non universals have been around for only a couple of thousand, going back to the Greeks, and have only become more widespread over the past 400 years or so. So I feel there is a strong basis for a cultural demarcation here, it's not as fuzzy as you suggest. Our modern society is built on the knowledge contained in the non universals.

There is implied here a view of history that there is such a thing as progress as we move from hunter-gather, through feudal, through capitalist society and beyond to who knows(?). However, I wouldn't describe it using the terms ("white man's burden" "educating the savages") that you are using. However, I agree with you that this view of progress is disputed, eg. through the lens of cultural relativism or post-modernism. That is part of the problem, we have lost sight of what progress is. I do see both passive and sometimes active resistance to the suggestion that the non universals do in broad terms describe what our education system ought to be about. That is part of our current culture that everything is relative and ought to be equally valued. Year 11 Bushwalking and Advanced Maths are given the same value on an educational certificate; that is not progress IMO.

@teapot:

"I find "universals" and "non-universals" to be a very poor choice of words. "

I think you misunderstand the use of "universal" here.

Each and every human society in history has had language. There really are no exceptions. This is a real universal. With really few exceptions, all children enter school while they already speak a language and will "improve" easily. Those that do not speak a language are considered handicapped in all societies.

On the other hand, writing has been invented maybe only twice (in the middle east and in meso-america). Every society that knows how to read and write received this knowledge from some other people. That is NOT a universal. And hardly any child that enters school can write. Actually, children are send to school for the purpose to learn to read and write.

So this has nothing to do with "within" and "between" cultures. A universal is meant to be as universal as having eyes and feet. A non-universal is as non-universal as wearing a hat or braids.

Winter

"The term universals is well established from anthropological studies."

I realize that -- The problem is, what is an accepted term in one area of study may be completely foreign to another area. Anthropology by its nature sees things as they are developed in societies over very long time, while teaching has to deal with the same knowledge learned by individual in a matter of years while dealing with a society that is most likely more developed than most of societies that anthropology studies.

Sometimes "learning" of the whole society and learning process of an individual follow the same path, sometimes they are completely different. Use of term that describes development of society to describe development of an individual seems to imply that modern child's knowledge is an equivalent of knowledge of an adult from an earlier point in history. When dealing with countries that are perceived as "primitive" and "underdeveloped" this also creates an opportunity for all kinds of insults and misinterpretation, especially with "democracy", a political term, in the mix (in US the idea of "democracy", a non-universal, is completely subverted by "patriotism", a representation of universals "culture" and "differences over similarities").

Well, we don't have to teach all the non-universals right away. We can start with reading, riting, and 'rithmetic. Then if the student has some aptitude they will have a chance to discover additional non-universals on their own. Global communications systems will help there, something our ancestors did not have.

teapot, you are still reading something that Alan nor Bill didn't write, and effectively derailing the discussion (if there is one).

Alan and Bill are saying there are ideas that are harder to learn and ideas that are easier to learn. And, these are equally true to the students anywhere including developing countries. Neither is claiming that all non-universal ideas are automatically important, although many of them are. They are not talking about bringing a developing country to be a developed country at all.

In this discussion, whether you like the terms or not doesn't matter. If your point is that people often misunderstand, yes, that point is well taken^^;

Thomas,

Did you realize that reading and writing (and most part of arithmetic) are "non-universals"? And the "discovery on their own" part is almost explicitly questioned by "Most people have lived and died on this Earth for 100,000 years without reading and writing". So, you need a better argument than just saying it.

Yoshiki: "They are not talking about bringing a developing country to be a developed country at all"

My take on this might be a bit different from Alan's (I don't really know). Part of my reason for posting about the non universals is to help develop parameters for this discussion. I think that is the stage where we are at. One reaction to the "knowledge explosion" is to say all knowledge is equal and the main thing is to show students how to find (any) knowledge. The web2.0 or school2.0 movement seems to be saying that. I disagree and think the non universals provide a sound basis for critique of that view.

I don't see this as just an educational discussion about what is more difficult, that is part of it, but there is more to it. These ideas are connected intimately with the notion of development and as such they do have political implications, both historically and contemporary - the capitalist revolution against feudalism was fueled by the non universals (democracy, science, maths etc.).

Carl Sagan pointed out in his 'Cosmos' series that the Greeks were very smart but the slave nature of their society (ie. not democratic) held things back from further development. That is just one example. Another is the essay by the philosopher Daniel Dennett about "Postmodernism and Truth": http://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/papers/postmod.tru.htm

It's difficult to know what reliable data is but one impression I get is that some developing countries regard maths and science (for instance) very highly whereas some developed countries that have benefited from their maths and science knowledge for centuries are now become complacent about this knowledge. If you already have (some) development then it's easier to become complacent about it, to take it for granted. Following the Sputnik scare (1957) there were various efforts to promote science and maths more vigorously in the USA but after a while complacency (and confusion about direction) reasserts itself.

At any rate, I think the countries or education systems who treat the non universals seriously will prosper relative to those who don't. And by prosper I don't only mean prosper economically.

teapot:

"When dealing with countries that are perceived as "primitive" and "underdeveloped" this also creates an opportunity for all kinds of insults and misinterpretation, especially with "democracy", a political term, in the mix (in US the idea of "democracy", a non-universal, is completely subverted by "patriotism", a representation of universals "culture" and "differences over similarities")"

Well, the US is a democracy, warts and all, where people of mixed cultural background and women can aspire to be President - and some countries are not. btw patriotism only arose with the nation state. There are still some people in the world who don't know what country they live in, who don't understand the concept of the nation state. Are you promoting these people as "noble savages" from whom we have much to learn?

I'd prefer to look at it this way. There are ongoing tensions between universals and non universals. We could have better democracies where the mass media promotes the real issues more than the current "newsworthy issue" (the pregnancy of the teenage daughter of a potential VP). That would be a worthy goal of an education system and it could start by treating its students as citizens who are capable of understanding and discussing these issues.

In some countries people are so complacent and fed up with the democratic process they can't be bothered to vote. In other developing countries they risk their lives to vote (eg. Zimbabwe, Iraq). In other countries they languish under fascism (eg. North Korea, Myanmar / Burma) Irrespective of your political view, this is a rich issue for the education curriculum, something to argue about and for students to gain real knowledge.

"Well, the US is a democracy, warts and all, where people of mixed cultural background and women can aspire to be President - and some countries are not."

I have a very dim view of both "democracy" implementation in US, and American people's belief that since they have it, they should not bother checking if government is actually serves all of them or oppresses most of them to serve the few, however this is an entirely different discussion. In the context of education, the very last thing we need is yet another attempt of "spreading democracy" by a US-based organization -- as a foreigner I can assure you, it will not be taken well in any place outside US that I am aware of. There are plenty of things in education that do not overlap with political propaganda and ideological wars.

"btw patriotism only arose with the nation state. There are still some people in the world who don't know what country they live in, who don't understand the concept of the nation state."

This is not relevant to the core of the issue -- in the context of "us vs. them" nation state is merely one form of defining a group of people that is may be opposed to, or compared with the others. Being applied to the nation state instead of some other group does not make it a different concept.

"Are you promoting these people as "noble savages" from whom we have much to learn?"

Absolutely not. I just want to prevent attempts to use educational programs to propagate ideology -- plenty of failures happened because of this.

"I'd prefer to look at it this way. There are ongoing tensions between universals and non universals. We could have better democracies where the mass media promotes the real issues more than the current "newsworthy issue" (the pregnancy of the teenage daughter of a potential VP). That would be a worthy goal of an education system and it could start by treating its students as citizens who are capable of understanding and discussing these issues."

I am sure, better understanding of science, math, and literature would go a long way of promoting better understanding of those issues.

"In some countries people are so complacent and fed up with the democratic process they can't be bothered to vote. In other developing countries they risk their lives to vote (eg. Zimbabwe, Iraq). In other countries they languish under fascism (eg. North Korea, Myanmar / Burma)"

As I have mentioned above, I strongly disagree with this. My opinion is that US is a great example how democracy can be completely subverted by spreading ignorance within the society and lacing all forms of culture and popular discourse with propaganda. In supposedly non-democratic country an intelligent person knows whom he has to persuade to implement some idea (and usually people who have to be persuaded are bored and therefore receptive to ideas presented in some form). In American "democracy" it's either a bunch of corporate executives (complete with their antisocial personality disorder that earned them their positions) or tens of millions of ignorant people (who understand no argument but appeal to authority). If I had any hope for American society actually utilizing democracy for the originally intended purpose, I would support improvement of American public schools, however at this point in history it looks like a futile endeavor.

"Irrespective of your political view, this is a rich issue for the education curriculum, something to argue about and for students to gain real knowledge."

US has a long history of weakening foreign countries by spreading its (granted, attractively looking) ideology while the people were insulated from actual contacts with US, then taking them over by military, economic or political means. When given a choice between supporting goals/methods of CIA and Microsoft, I would rather choose Microsoft -- and my opinion of Microsoft is well known on the forums here.

Teapot said "I am sure, better understanding of science, math, and literature would go a long way of promoting better understanding of those issues."

That is the core of my problem with this upper level analysis of what should be taught in schools. I'm student teaching in a rural area in a school that is "one of the richest." These 4th graders do not know their math facts (forget about fluency) and are asked to add large numbers. These kids can not read with any fluency, but are told to silently read to themselves for 20 minutes a day in class. These kids are still learning to put a capital in the beginning of the sentence and period at the end but they don't know that the word "I" is capitalized and can't spell, let alone write, worth a darn.

Until the basics are taught to mastery, they will struggle struggle struggle. And yes, you can teach to mastery in an engaging way.

hi dickey45,

For the past 10 years plus I have taught in disadvantaged schools so, I agree, the issues you raise are real problems. Maths and Science are often poorly taught in many schools. There are a couple of trends in Australia that are worth identifying:

residualisation - Private school growth is encouraged by government and have the right to kick out students, whereas the government schools are legally obliged to keep difficult students but not given the resources to cope with them

curriculum integration - When I talk to the children of friends who are at Primary school I get the impression that maths is mainly dealt with in the context of a broader integrated cross curricular topic. Then I notice that recently arrived immigrants, from Poland, know far more maths than Australian kids. It is treated more seriously in some countries and school systems.

Focusing more on the basics (maths, science) is not at odds with the non universals list